One of my absolute favorite things to come out of 21st century entertainment is Black Mirror. Headed and largely penned by presenter and professional geek Charlie Brooker, the anthology series traces disconnected stories within a sandbox universe similar to our own. The big difference? Technology is much more active and versatile than our own.

It can be gratifying for those viewers tired of Instagram “influencers” and heads hunched over smartphones during social outings to see the wired among us get our comeuppance. Various episodes see social media addicts lose their social standing in a public meltdown. Vicious hashtag games turn around and sting their participants, and talent show addicts swept into the true nastiness of the entertainment industry.

But for those watching for that gratification – the self-proclaimed luddites feeling happy that a TV show is taking their side – I have a bit of sad news. Technology is not the villain of Black Mirror. If anything, technology is the one innocent party in the entire series. It’s a show about us, and who we look at at when the screen goes dark.

A God or a Demon

In the 1960s, Japan launched the first-ever giant robot anime, Tetsujin-28. (Western fans may know it as Gigantor.) Its localized setting was The Future, but the original story was far grimmer. It took place ten years after World War II, when the show’s source manga was written, and the friendly robot led by boy detective Shotaro was a literal bomb. Designed by his father as a retaliation against the Allied forces, Tetsujin-28 is repurposed to help fight monsters and rebuild Japan.

There was one other major line of action for the show: keeping the robot’s remote control in Shotaro’s hands. You see, Tetsujin-28 had no inherent morality. He was simply a robot. Anyone with the remote could use him for anything. He wasn’t a good robot or a bad robot. He just was.

Go Nagai followed up with this in 1972 with his history-making anime Mazinger Z. The show put its pilot, the reckless Koji Kabuto, directly into the robot for the very first time. And while there were many other advances and new plot points, the main focus was the same. The robot was a piece of technology, free of morality, and fully at the disposal of whoever used it. Even its name, “Mazinger,” is a reference to the fact that it can be a demon (ma) or a god (jin) based solely upon who uses it.

This point – the objectivity of technology and its morality being a subject of its user – tends to come up at very specific points in history. For Japan, it was in the wake of a war. And for Black Mirror, the new tech-driven series of the Western world, it’s amidst both horrible crimes and benevolent acts being facilitated by the advances we have adopted.

What’s in a Name?

Charlie Brooker chose the name “black mirror” to evoke a very specific moment. It’s one we all encounter several times a day. When you turn off the television at night, or you finish a video game, or you shut down your computer or phone, you see yourself for a brief moment reflected in the dark screen. The technology is “off.” It’s doing nothing. But for a brief moment, you are afforded a look at yourself via it. That is the literal “black mirror” in question – your shut-off screen, reflecting yourself back to you.

With Facebook full of memes about the Better Days, about having to actually go to your friend’s house to ask them over, about how people Just Don’t Talk Anymore, there comes a certain sort of craving for seeing entertainment that shows us that technology is just as bad as we think it is. We (a universal “we” – your writer was born in 1981 and has never not had access to a computer, and your writer doubts many of you think this way) want to be agreed with: Internet bad. Facebook bad. Smartphones bad. Kids These Days. Et cetera.

And a show like Black Mirror, showing a world coming apart at the seams in the midst of eye implants and recreations of dead loved ones from Twitter accounts, seems to feed just that. But look deeper, read deeper, and the technology is nothing but a conveyance.

Black Mirror is the story of what we do to ourselves and each other, with technology as the unwilling accomplice.

From Downing Street to San Junipero

Netflix now allows us to watch Black Mirror in its entirety. Starting from its two three-episode UK series, followed by its Jon Hamm-starred “White Christmas,” and then branching out into more experimental, longer Netflix-produced seasons. The first episode, “The National Anthem,” was a turn-off for many. It depicts a frighteningly modern story of blackmail that required no suspension of disbelief to immerse oneself in. That episode alone has scared many off. But diving deeper begins to show us the improbable tech that leads to our human studies throughout the show.

The higher-end tech of Black Mirror may make headlines when something similar makes its way into the real world. But largely, it is not intended to be believable.

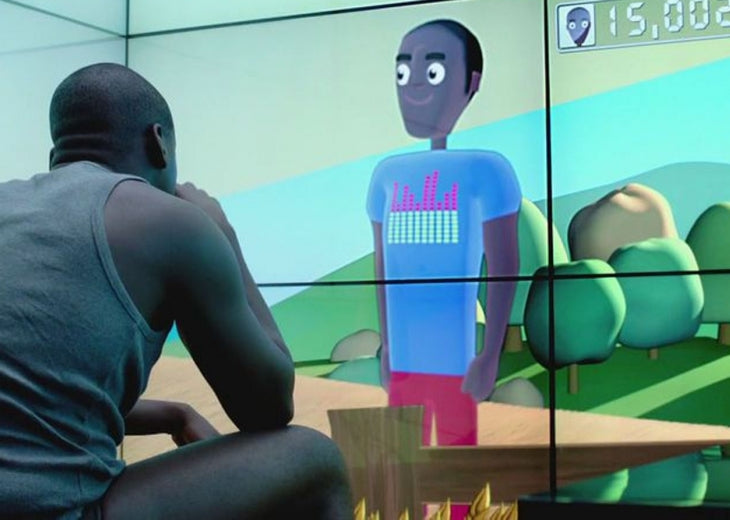

Stories like “Playtest” – about a man jacked into an inescapable horror game that draws on his personal fears – are not cautionary tales of the future of technology. They’re about us, here and now. “Playtest” may look like a damning examination of augmented reality taken too far. But look deeper and you see the true story: the human nature of fear, and how we seek out harmless thrills while avoiding life-altering problems.

The number of people who approach Black Mirror as a critique of technological progress is dwindling as more episodes come out. Dark but optimistic pieces like “San Junipero” and “Hang the DJ,” along with the socially aware “Black Museum,” make it harder and harder to neglect the truth of the series.

I often say that if Black Mirror doesn’t call you out at least once, it’s not doing its job. It’s not the show’s job to make us deeply uncomfortable. But mirrors are there to let us see our own reflection, our assets and our imperfections. And, just as technology has always done, Black Mirror itself will continue to show us what we always have been – for better or for worse – amplified with the power of computers.

Comments are closed.