So, confession time: I’ve never in my life played more than five minutes of any Five Nights at Freddy’s game.

I can’t. I have epilepsy and anxiety, so it’s a no-go despite my love of nightmare fuel and the “ruined childhood” aesthetic. I’m fine watching theory videos and Let’s Plays, so I can at least get my fix that way. I was never big on that particular brand of survival horror, so I wasn’t missing much. But the slowly unwinding lore when it first came out had me fascinated. (Anyone who’s read my previous articles will understand this — I love taking stories apart and looking at all their individual pieces.)

This continued into recent additions, all the way up to the latest game and the supplementary books. The story has grown. Like, a lot. Gaming channels will make entire playlists devoted to cracking the story open. And it’s a story that’s alternately heartbreaking, horrifying, and hilarious.

But . . . as a writer watching the story evolve one Steam game at a time, I noticed something: the story constantly fell prey to being told in pieces, with audience feedback in between. And that has its good points and its really quite horrible actually points.

Even if you don’t like horror, video games, or animatronics, if you consider yourself a storyteller of any kind, you should probably at least follow the progress of Cawthon and his most popular child. Because there are two interesting stories at work at the same time.

The Early Days

Years ago, Scott Cawthon worked both at Christian cartoon company Hope Animation and independently as a game dev. All of his work was all-ages appropriate, with much of it (including an animated version of The Pilgrim’s Progress) being overtly religious in nature. He also created Sit ‘n’ Survive, a resource management game with a camping theme.

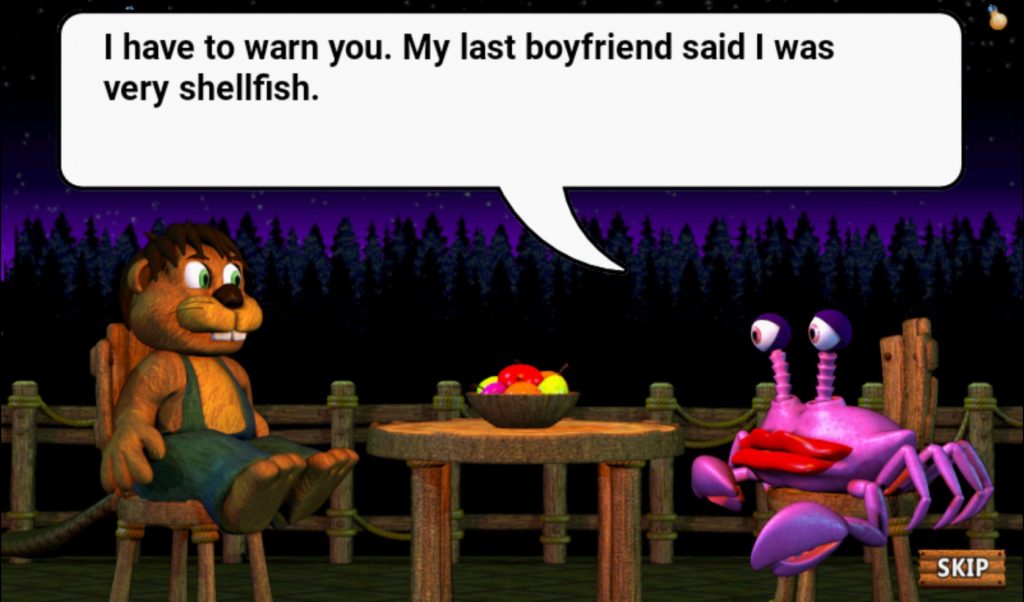

His games were . . . not terribly well received. One, Chipper & Sons Lumber Co. (screencap above), garnered heavy criticism for sporting characters that looked like creepy animatronics. This almost led to Cawthon giving up game development. But instead, in a move of passive-aggressive creativity rivaled only by Sam Raimi making Evil Dead 2, he went “I’ll show you creepy animatronics.”

And thus, Five Nights at Freddy’s came to be.

Broken down to its most basic elements, Five Nights at Freddy’s was a horror version of Sit ‘n’ Survive. You, a night watchman at a kids’ pizza joint, held a six-hour graveyard shift for one work week. All well and good, except you discover that the pizza place’s animatronics have a “free roam” mode left on at night For Reasons, and if you’re not careful they might kill you. Make it through five nights, and you get a decidedly 80s paycheck and a sixth night. Make it through that, and you get fired.

Gamers and YouTubers loved FNaF for its bizarre concept and occasional understated humor. And then people started finding. Things. In the game. Listen closely to your training tapes, check newspaper clippings, and an actual story started to surface: one of children murdered in the pizzeria and stuffed inside the specially designed animatronic suits.

Oh, and there was a random yellow version of the main mascot who’d appear and flash IT’S ME at you in text.

Now things were getting interesting.

The Story Continues

Only three months later, a sequel came out. And whether this was always the case or fan reaction encouraged him to go there, Cawthon filled this game with even more background lore. Players would occasionally find themselves playing 8-bit minigames revealing more story. Four months after that, the third game came out, taking place in the not-too-distant future at a haunted attraction based on the pizzeria. Again, there were more minigames, and the story really got rolling. Players who found every extra discovered the story of the game’s ghost children taking revenge on their murderer (stuck in a springlock suit of his own). And if all went well, you could achieve the “Happiest Day” ending, in which the ghostly kids found peace.

A month later, Cawthon began advertising “the final chapter” of the Five Nights at Freddy’s saga. And three months later, well ahead of its Halloween 2015 release date, Five Nights at Freddy’s 4 hit Steam. This game was unique in that you played as a child, haunted by nightmares of the animatronics in your own room. Cut scenes revealed a boy who received massive brain damage after being bitten by one of the characters, eventually (it seemed) dying surrounded by plushies of the core four mascots. Toys scattered around the levels matched other visuals throughout the games. It seemed fairly certain that the whole saga had been a child’s tortured dream.

Baby Don’t Hurt Me

In later interviews, Cawthon spoke vaguely of the Five Nights at Freddy’s 4 ending, also saying the story evolved from its original trajectory. He feared that audiences wouldn’t “accept” what he had in mind. And while he never said outright that the upshot was all a child’s dream, scattered hints and statements invited players to infer it very strongly.

But that wasn’t the end.

FNaF World rolled around afterwards, seemingly a cheery RPG featuring cute versions of the Freddy’s team. But cracking it open led to an odd discovery. A late scene revealed a dying man at his desk, haunted by his creation: a glowing-eyed child called “Baby.”

Baby would become the star of Sister Location, a new game that stretched the story even further. And this seemed to contradict all that FNaF 4 told us. So . . . it wasn’t all a child’s dream? Apparently not. Now we delved deeper into the story of William Afton and his partner Henry, the creators of the animatronics. And from there, it became a tangled web of murder, ghosts, and odd experiments.

The line expanded further still: three tie-in novels were treated as an alternate universe, then turned out not to be. A guidebook hid more hints throughout. Then came Freddy’s Pizzeria Simulator and Ultimate Custom Night, two seemingly frivolous games that offered up even more back story.

So where do we stand now? Well, it seems both the creators are dead. William Afton (as the monster Springtrap) is in hell or purgatory being tortured by his creations for all eternity. Both of them had at least one kid who was a robot or became a robot or something. There’s a thing called “Remnant” that was distilled from ghost children and used to make the animatronics of Sister Location. And the rest depends on which YouTuber you’re consulting.

So by all appearances, Cawthon dropped his original concept, retrofitting it to a new story. A good story, but one that has fallen prey to a real danger of writing.

What’s It To You?

When I say that “storytellers” should know these events, I mean all kinds. Not just writers or comic creators or actors. I mean DMs. Online roleplayers. Anyone who, in some way, creates a story that another person will see. Because what the world of FNaF has become is due largely in part to tweaks on the fly.

First off, there was almost certainly never a long-term concept for this. Remember, Cawthon was halfway out of being a game dev when he released the first game. It’s unlikely he was prepping a multimedia franchise so much as seeing what he could do. And when he did approach an ending, it was the “it was all a dream” angle. (Incidentally, that approach isn’t always bad. Like any storytelling element, it can work if addressed well.)

Cawthon has mentioned that if he saw theorists going way off base, he’d course-correct in the next game. Which is a positive opportunity in serialized storytelling: you can tell when something isn’t getting through. And that’s something to note and use. But then there’s fan reaction to an ending. Would fans have accepted the “dream ending” to FNaF? Or is this spun-out tale of ghost-robots the “right” approach?

We’ll never know.

Sticking to your guns in a serialized story is a tough ask. If your fans aren’t responding well, you sort of want to lead them somewhere they’ll like. And fans have had fun picking apart the new continuity of Five Nights at Freddy’s, from timelines to who the children are to who the heck is in Golden Freddy. But all of this has led to a story tripping over its own canon. And once in a while, the seams show.

I sometimes wonder if the man dying at his desk as Baby looked on wasn’t a bit of Scott Cawthon himself.

I love the horror of FNaF and I love the story. But it makes me realize that, save for the odd D&D campaign, you need to be careful how much you keep your ear to the ground when telling a multi-part story. Some is good. Too much could get you tripped up and fearful.

Comments are closed.